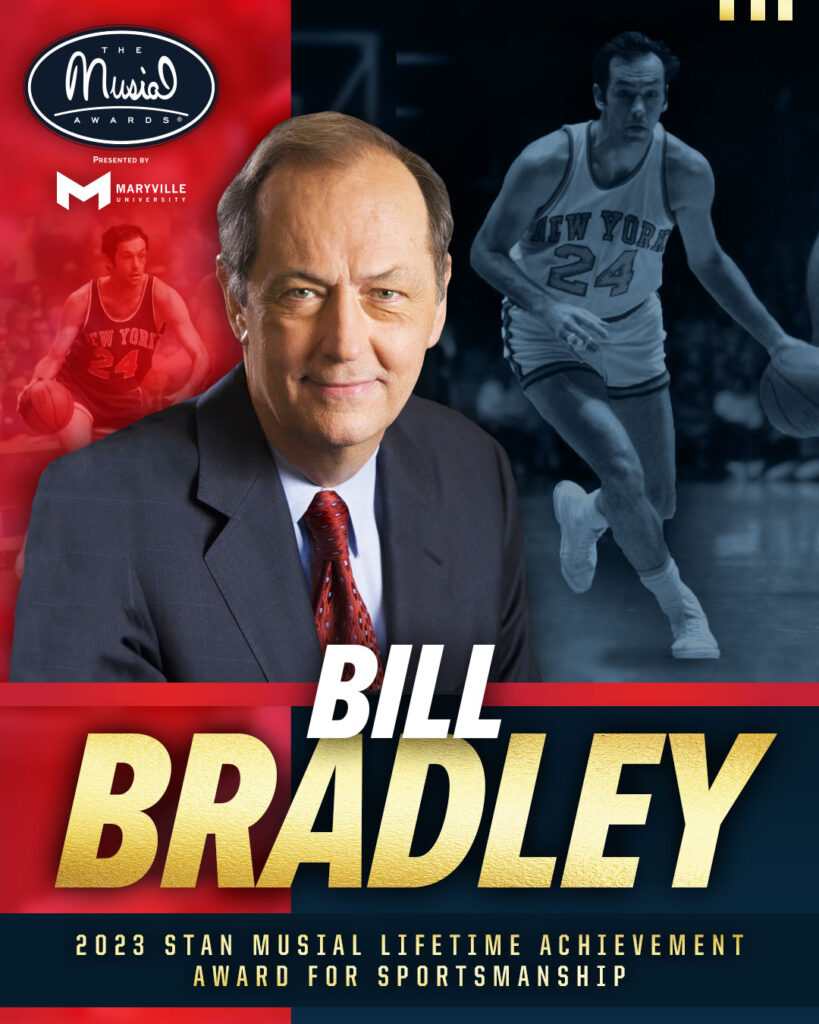

Bill Bradley

Like so many kids growing up around St. Louis in the 1950s, Bill Bradley was a Stan Musial fan who just wanted an autograph. And, as with every young fan, Stan obliged Bill, according to The New York Times.

Like so many kids growing up around St. Louis in the 1950s, Bill Bradley was a Stan Musial fan who just wanted an autograph. And, as with every young fan, Stan obliged Bill, according to The New York Times.

For most kids, that was that.

But Stan and Bill met again, a decade later, at a White House celebration following the 1964 Summer Olympics. Recently retired, Stan was serving as special consultant to the President on physical fitness. Bill had interrupted his academic career at Princeton to win a gold medal in basketball, and as The Times reported, “was thrilled” to shake Stan’s hand this time around.

Given Bill’s reaction to winning the Stan Musial Lifetime Achievement Award for Sportsmanship, the thrill isn’t gone. Far from it. “To be recognized in the same category as the great Stan Musial is truly an unexpected and remarkable honor that I am humbled and proud to accept,” he says.

Bill has left his mark in sports and political arenas. But before he studied in the halls of Oxford, pounded the hardcourt of Madison Square Garden, or legislated on the floor of the U.S. Senate, the foundation for his achievements was laid in Crystal City, 35 miles south of downtown St. Louis.

“You can live in a lot of places,” Bill told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 2011. “But the place where you grew up never leaves you. It’s in your bones.”

His first teacher on the court was Crystal City High coach Arvel Popp, who preached hard work, resilience and discipline. Bill scored 3,068 points at Crystal City and was twice named an All-American. But he says the years with Popp were more valuable for “experiences that transferred to academics: spending the time to get the work done, giving yourself the time to develop your talents.”

Bill has taken his time, often looking past the easy way to do things the right way. After high school, he turned down 75 scholarships, instead paying to study and play basketball at Princeton. He interrupted his college career when the Olympics came calling, returning with a gold medal, then became the 1965 AP College Player of the year and MVP of the Final Four.

Next, he put an NBA career on hold to accept a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford, then serve in the Air Force Reserve. Finally, in 1967 he began his pro basketball career, becoming an integral member of the only two NBA championship teams in New York Knicks history. Throughout the journey, he maintained his love of the game. Of that second championship season in 1973, he writes: “In plenty of games, I played simply for the joy of it, shooting and passing without thinking about points.”

But for those keeping score, Bill tallied 9,217 points in his 10-year career and was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1983. By then, he was four years into his first term as a U.S. Senator representing New Jersey. “I realized this wasn’t much different than the Knicks’ locker room,” he told the Post-Dispatch. “As a legislator, you’re trying to establish a team that can get the votes.”

After three terms in the Senate, he ran for President in 2000, making Crystal City one of his first stops. When the Democratic nomination went to Al Gore, however, Bill retired from elected office.

Since then, he has shared his life lessons by authoring seven books. Among them is Values of the Game, a collection of essays filled with anecdotes and examples of how the lessons of sports translate to life. Among the essay topics are Selflessness, Respect, Leadership, Responsibility and Resilience: words often used to describe Musial honorees. His observations hit home, simultaneously personal to Bill Bradley and universal to all lovers of sports.

“Each time a (parent) takes a son or daughter to the playground to shoot baskets for the first time, a new world opens,” he writes, “one full of values that can shape a lifetime.”